Feeding the world: the problems we need to fix

· 6 min read

An open letter signed by 150 Nobel Laureates on January 14th once again points to the urgent need for food-systems transformation to address growing food insecurity. While the letter is well intentioned, the framing unfortunately reinforces the myth of “too many people, not enough food”. The emphasis is primarily made on increasing food production, at the expense of the need for improved distribution, access, more sustainable food production methods, drastically reducing food loss and waste and transitioning to planetary health diets. So, while the effort fueling the open letter was noble, we need to, once again, clarify and refine collective understanding if we are to move forward. Other authors have already begun to engage to help reframe and clearly identify the problems we need to fix.

Let's challenge the outdated assumptions that prevent us from fully understanding the need for food systems transformation. Let's assess our current situation and explore what the future might hold. Let's focus on two interconnected issues: reversing growing food insecurity and addressing environmental degradation. While optimizing food production, especially for the world's poorest small farmers, is crucial, only a systemic view of the global food system will enable us to design interventions that create lasting, transformative impact.

What assumptions do we routinely bring to understanding of food-systems? Three issues get typically overemphasized or overlooked:

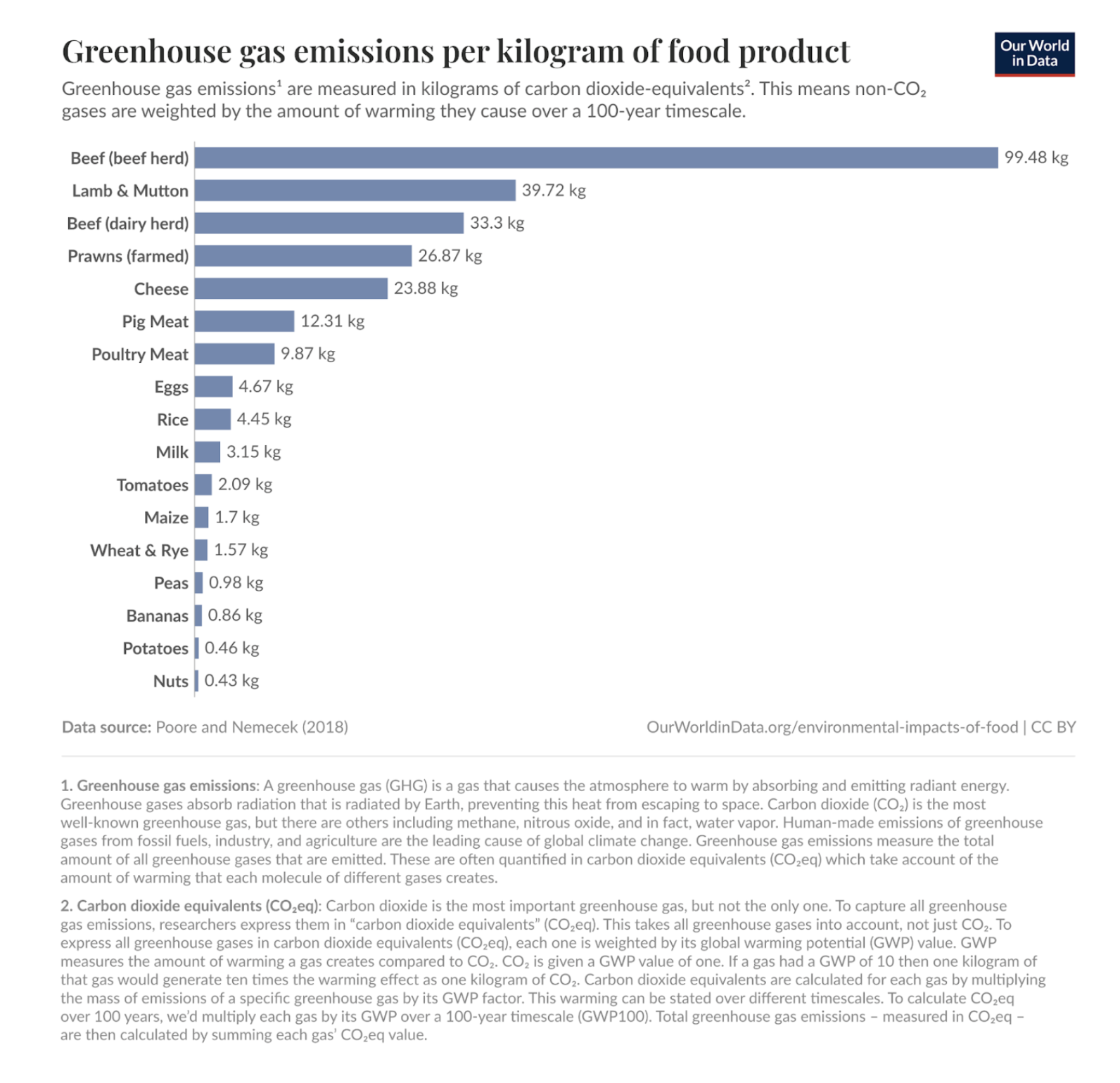

The world therefore produces plenty of food, but it’s not getting to the people who need it. Furthermore, much of the world’s food producing resources are used to feed livestock, produce biofuels or go to produce highly and ultra highly processed junk food. Add to this the fact that at least one third of food produced in the world goes to waste contributing to about 10 percent of the world’s greenhouse gases. This spoilage is either due to the lack of simple post-harvest technologies such as granaries and cold chain in the global south, or inappropriate regulations and consumer education and behaviour issues in wealthier jurisdictions and communities. It’s a question of access, not supply on a global level. And future projections depend on our diets.

Structural inequality conditions access to food as a result of many “isms” - sexism, classism, racism, ableism and some would even add capitalism itself. And the impact of armed conflict on the food-system is absolutely central in terms of destroying supply chains as we see in Sudan, Gaza and other parts of the world. Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen’s work on the Great Bengal Famine clearly made the link for us and, though we see cursory reference to the link between war and food insecurity in the recent open letter, we don’t frame peace-building enough into our discourse. As the World Food Program indicates “Conflict is one of the main, and most devastating, drivers of hunger.” Needless to say, the environmental impacts of armed conflict and its aftermath is also devastating.

We can imagine two scenarios emerging: one pessimistic and the other optimistic. At the present moment, the future of the global food system is looking rather apocalyptic with denial about climate change, loss of biodiversity and broader environmental catastrophes, unending armed conflicts and the seeming destruction of democratic institutions. We can envisage a future where the wealthy continue to hoard resources, including fresh and healthy food, with the masses reduced to highly and ultrahighly processed, inexpensive “filler” leading to even more diet-related disease. At worst, we can envisage our own, eventual annihilation as a species if the current trends continue (see Figure 2).

But I and many others prefer a more optimistic vision for the future. Planetary Health Diets, which are more plant based and far less highly and ultra-highly processed foods are increasingly recognized as part of the solution to the growing health and environmental crisis. Likewise, the “One Health” approach, which recognizes the interconnections between human, animal and environmental health is an appropriate metanarrative to reduce and mitigate the negative environmental and health impacts of the current food system. At the more tactical level we’re seeing concrete steps forward such as school food programming in Guinée that prioritizes child nutrition as well as positive environmental impact and sustainable livelihoods. In the case of South Korea - a high income country - this type of school food programming was used to help drive food-system transformation. It can be done.

Understanding and transforming the current global food system - including its devastating human and environmental impacts is fundamentally a question of more equitably distributing power and control. And food security is primarily a question of environmental and social justice. It is not about overpopulation and increasing food production using conventional methods to supply the industrial diet, both of which are currently destroying the earth and our health. As both Simon Gupta and Jennifer Clapp and many others have argued, we need an urgent transition to agro-ecology.

Including the voices of Nobel Laureates such as Amartya Sen whose work on famine clearly demonstrated that food supply is rarely the issue behind food insecurity would have been wise. At 91, he is still lucid and active and would have helped refine the letter in a manner that does not roll us back to reinforce old myths. Likewise, consulting and including Nobel Peace Laureates given the devastating impact of war and armed conflict on food insecurity, would have likely yielded a more holistic framing. Let’s hope for a version 2.0 of this letter in the near future.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Yury Erofeev

Food · Agriculture

illuminem briefings

Sustainable Lifestyle · Food

illuminem briefings

Sustainable Lifestyle · Food

Axios

Food · Sustainable Lifestyle

The Independent

Climate Change · Food

Forbes

Sustainable Lifestyle · Food