· 9 min read

The recent wind-driven wildfires in Southern California destroyed or damaged well over half of the residential structures along with nearly half of commercial buildings, schools and churches in Altadena and Pacific Palisades. Some houses and streets remained intact while everything around burned down, leaving residents grappling with living in the midst of a toxic wasteland that may take years to recover.

This was largely a replay of the 2023 Maui wildfire which burned much of the town of Lahaina. When wind-driven wildfires cross over into urban areas, they generally destroy the fabric of entire communities. Rebuilding can be slow, and many residents may not afford the costs involved. A year and half after the Maui fires, only five out of the more than 1500 impacted properties have been fully restored. Rebuilding the damaged communities will be even more difficult.

The response to these catastrophes seems focused very much on fire-hardening individual structures – but limited by cost and scalability – while mostly ignoring the question of how to preserve the interconnected and more complex communities. This bottom-up approach, focusing on individual structures, assumes the whole will fix itself. A more cost-effective and scalable solution might be a top-down approach, where the community itself is the unit that must survive wildfires.

A lack of vision for fire-resistant communities

California Governor Gavin Newsom’s executive order requiring an ember-resistant zone (known as “Zone 0”) within five feet of buildings located in the highest fire risk zones can only help, but it feels like a missed opportunity when a larger vision for fire-resistant communities might have been well received not just in California but also across many of the fire-prone western states in the US.

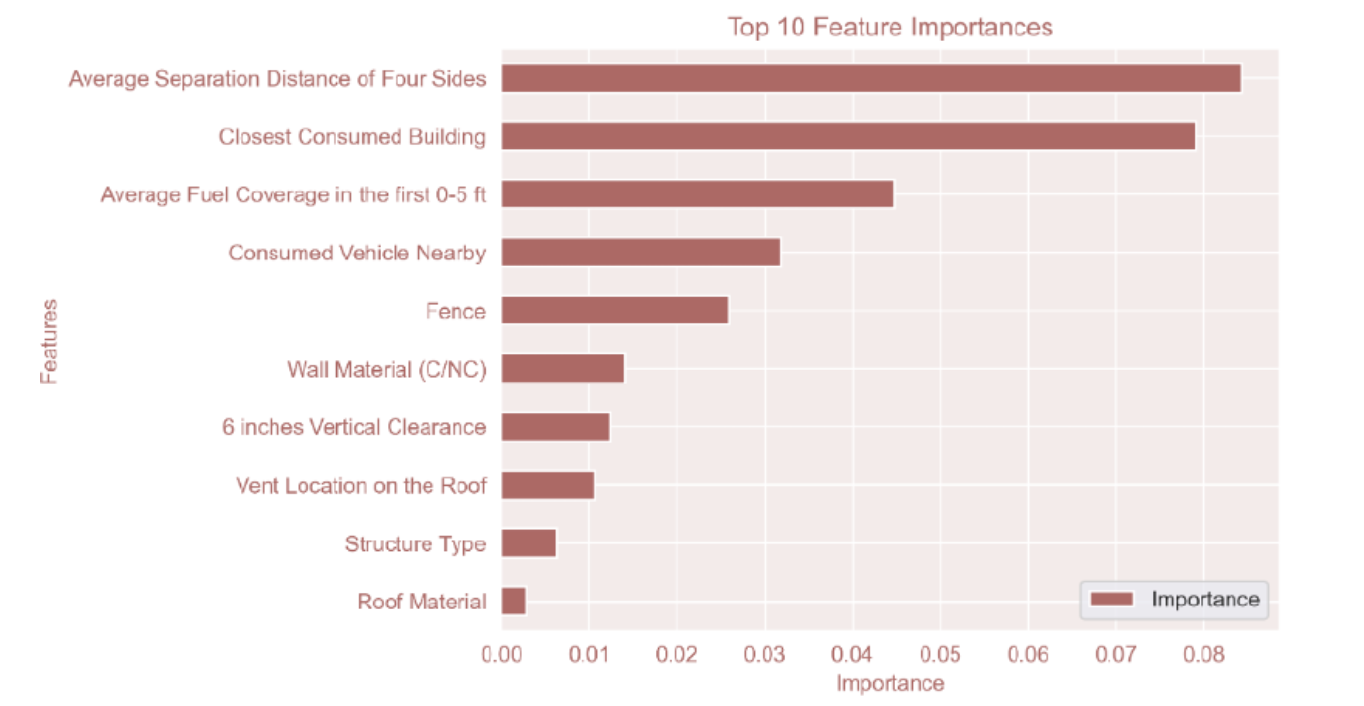

An insurance industry study following the Maui fire identified ten features of buildings and immediate surroundings with the greatest impact on fire spread. By a wide margin, the spacing between adjacent structures was the most critical factor determining fire spread, but this is obviously unchangeable for the large stock of existing buildings. The potential intensity of a structure fire is so high that it can surpass the tolerance of even fire-resistant materials in adjacent buildings within 20 ft.

Source: Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS)

This just means that if some houses in a neighborhood catch fire, others are likely to ignite, and the fire will inevitably spread. This is especially true if the built environment is densely packed or if enough connective fuel paths (in the form of vegetation, fences, or vehicles) are present between buildings. When wind-driven wildfires reach urban areas, they destroy entire communities.

Expensive structure hardening involving new roof or wall materials cannot be mandated in existing buildings (except through building codes when upgrades are undertaken voluntarily) and might not be very effective in any case if the spacing between buildings is too small.

State governments are taking the easy way out and limiting themselves to requiring property owners in high risk areas to do the one easy and inexpensive item on this list: a minimal 5 ft defensible space around the properties. In Oregon, for example, this requirement covers just 6% of tax lots. This certainly adds a layer of protection to a relatively small number of existing structures and provides firefighters some safe spaces to do their work, but this scale of home fire hardening hardly matches the urgency of the moment.

Getting to the root of the problem

We limit ourselves to inadequate measures, like small defensible spaces, because of how we approach fire hardening. Instead of focusing primarily on reducing fire spread between urban structures – which all evidence suggests could still leave devastated communities in urban areas – we should go to the root of the problem and think about how to stop wildfires from crossing over to human communities.

We should be thinking about fire hardening and saving entire communities from wildfires, not just individual homes. We might find this to be both effective and more affordable in many cases.

Nationwide 32% of all US housing units were in the wildland-urban interface as of 2020, much of that adjacent to wildlands. These adjacent spaces are typically smaller towns and suburban neighborhoods that are often in the direct path of wind-driven wildfires. We will have to get smarter about where we build in the future, but we also need ways to protect most of what we have already built.

What if we empowered entire communities to proactively defend themselves from encroaching wildfires? After the 2018 Camp Fire destroyed the town of Paradise in California, studies showed that buffer zones (also known as greenbelts) located at the periphery of the community could significantly reduce urban ignition risk within the community and the expected losses from property damage.

Buffer zones: the what and why

One of the earliest papers on community buffer zones (Nowicki, 2002) proposed a quarter mile wide protection zone at the edge of the community to withstand flame lengths of 100 meters. This was primarily to prevent fire spread from wildlands to built structures via direct flame contact and radiant heat. Flying embers in wind-driven fires are another major pathway for fire spread and this would have to be accounted for as well.

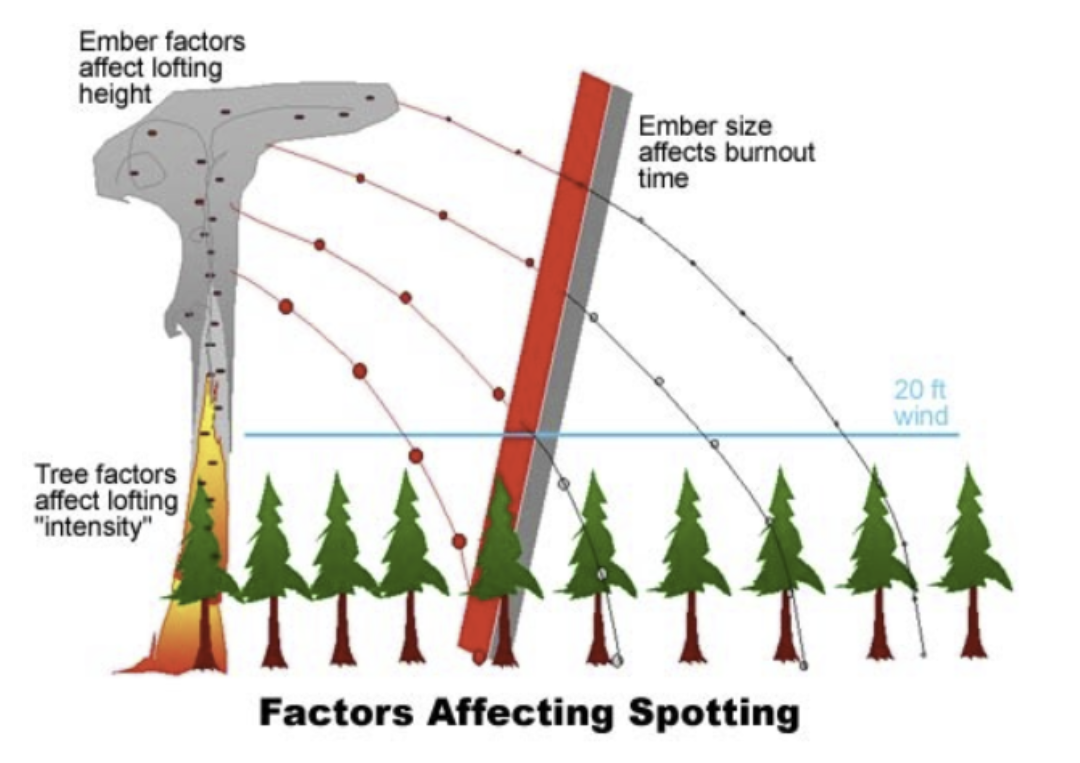

The Maui fire study noted that the main threat for homes bordering grasslands is from direct flame contact via connective fuels since grassland embers have a short flying range and burn out quickly. This was supported by another study in the Loess Canyons Experimental Landscape in Nebraska which used a fire simulation model to show that the median spotting (or ember flying) distances are approximately 1 km for grasslands and 3 km for woodlands under extreme wind conditions.

The picture below illustrates how the lofting height in a tree crown fire influences the ember flying distance as well as the possibility that some of the longest flying embers – which are also the smallest – might burn out before landing on combustible fuel.

Source: National Wildfire Coordinating Group

An experimental study by IBHS and the US Forest Service on ember production and transport from a variety of wildland and structural fuel sources found that the ember flying distance from burning shake roofs and engineered wood products used in building exteriors is 2-3 times the distance for embers from burning grasses and trees under high wind conditions. This suggests that embers might be a bigger problem within urban areas (due to the construction materials) than in wildlands, so the best place to deal with embers would be before a fire crosses into urban areas.

The study also found the distribution of flying distances to be positively skewed which makes shorter distances more likely than very long ones, so buffers could be designed for less than the maximum ember flying distance and still capture the vast majority of live embers.

These results indicate that a buffer width of 1-2 miles might be sufficient to greatly reduce the likelihood of a wildland fire crossing the buffer into a community through direct flame, radiant heat or ember transport even under heavy wind conditions. The actual width would depend on whether the community abuts grassland or woodland, the predicted future wildfire risk in that wildland area, and the likely extreme wind speeds and directions (including seasonal wind patterns like the Santa Anas).

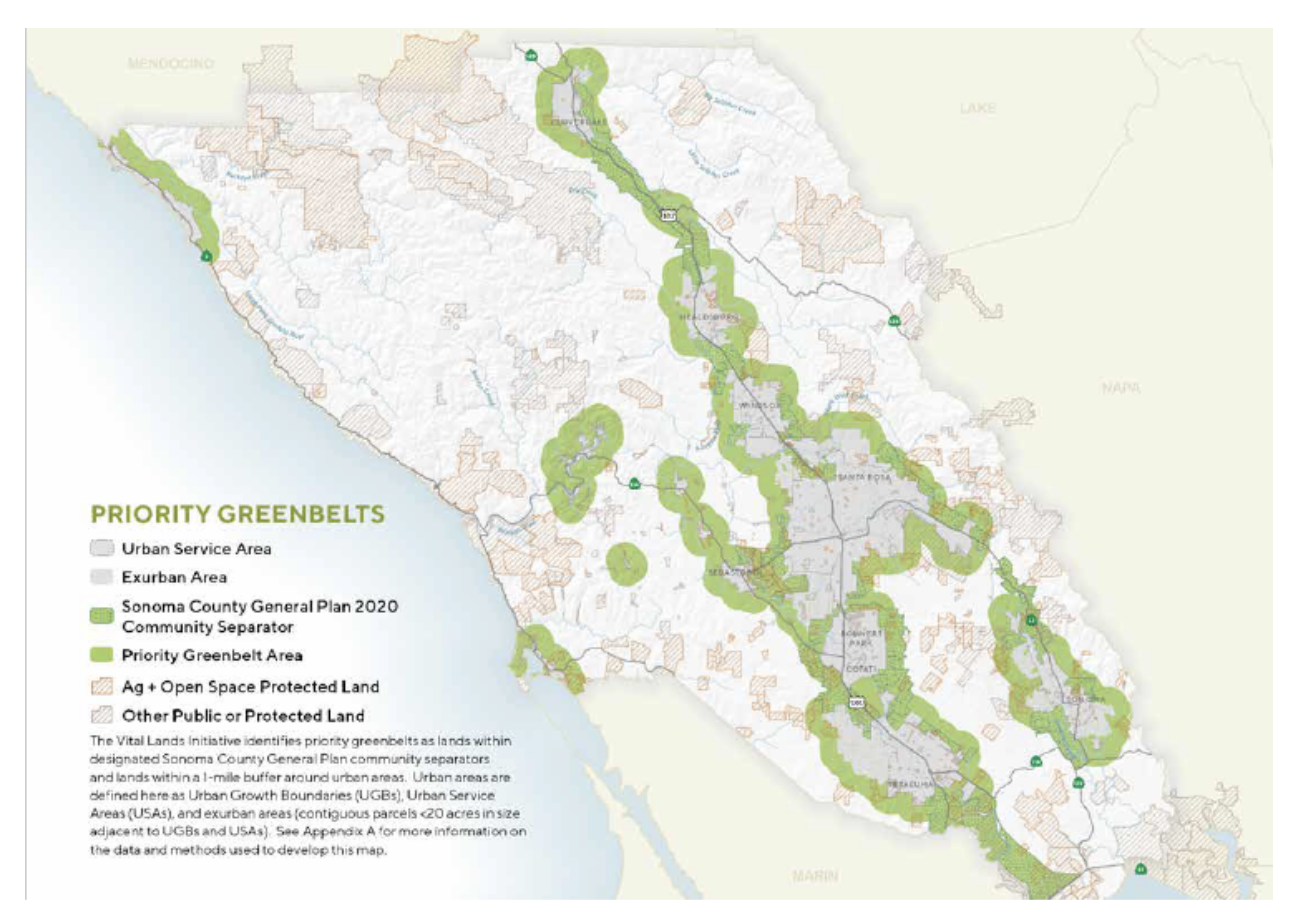

The map below illustrates the concept of a one-mile greenbelt buffer as proposed by Sonoma County in California to encompass all nine of its cities and several unincorporated communities to provide multiple benefits including wildfire risk reduction.

Source: Sonoma County Ag +Open Space

What would a community-centered wildfire solution look like?

As the climate worsens in the coming years and decades, we should expect an increase in the frequency and intensity of wildfires. We are not going to be living successfully with wildfires without working out effective community-centered solutions. Here is one possible version of what that could look like.

Buffer zones that are sized and located strategically could provide a level of protection that most communities do not have today. Additional buffers could also be located within the communities, if land is available, to break up connective fuel paths and limit ember transport between structures. Buffers could be especially effective if property owners in the community also implement every low-cost fire hardening step possible, including maintaining defensible spaces and installing ember-resistant vents.

Buffers might have co-benefits as staging areas and evacuation routes during fire incidents. They could also support recreational activities in normal times by incorporating walking and running trails. There would, of course, be private property in various locations that would need to be handled through purchases or easements where possible. Parts of public lands could be used on a state and national scale to systematically build buffers that protect nearby communities.

Buffers will come with a significant price tag for the land and maintenance. However, a simple calculation shows that a 1-mile buffer for a total length of 10 miles around a community of 10,000 homes could be 5-20 times less expensive than fully retrofitting all those homes with fire-resistant exteriors. Factoring in the potential costs of fighting large urban fires and then rebuilding the damaged structures, the return on investing in buffer zones could be quite high.

Public and private funding sources would need to be identified for the establishment and maintenance of buffers. Trees and other vegetation cut down to create the buffers could be sold directly for construction or biofuel production or pyrolyzed to produce biochar which can then be sold as carbon credits or as a soil amendment. Revenue generated from climate-friendly uses of the biomass could help fund a part of the buffer creation project.

Land developers could be asked to establish the necessary buffers for all new developments using the latest fire risk data and long-term wind projections. Community residents could be asked to contribute through affordable monthly assessments, which might turn out to be a good deal if it significantly reduces their wildfire exposure and increases their access to homeowners’ insurance.

Buffers as part of an integrated solution

Buffer zones should be seen as one part of an integrated solution to the wildfire problem. There are two other important components that should be implemented in parallel.

The first is reducing the likelihood of ignitions from power lines triggering wildfires close to human communities, which is a solvable technical problem. In addition to better maintenance protocols, this would include either carving out vegetation-free margins around power lines or burying the power lines, especially within 20-30 miles of any communities.

The second component is thinning out dry vegetation in wildlands through mechanical means or controlled burns, which is getting increasing attention now as part of healthy land management.

Working in tandem with these protective layers upstream that reduce wildland ignitions and fire spread, community buffer zones could add a new layer of protection and move us closer to preserving whole communities as human ecosystems.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.