Closing the financial disclosure loophole to prevent “emissions laundering”

· 4 min read

As Shrek once meticulously explained: “Onions have layers. Ogres have layers.” Likewise, finance can often have layers too. And without requiring financial disclosures to forensically follow the trail through the layers of financial intermediation, then regulators seeking robust climate-related reporting are leaving a giant loophole wide open. Forming a true and fair view of climate-related risks for banks means peeling back every layer until the underlying activities are revealed, understood and accounted for. This is one of the most essential principles that should be enshrined in the current review of climate-related financial risk disclosures by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision.

This is consistent with other well-established principles in accounting, starting with the concept of “Substance over Form”. This ensures that transactions and other events are accounted for by their commercial reality rather than their legal form. A recent example where this was called into question relates to an investigation of Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and their lending practices towards coal. Many of these institutions, including the World Bank’s private sector arm, the IFC, had set climate targets and made commitments to no longer finance coal. They reported to their stakeholders that they had stopped lending to coal. However, investigative work carried out by research teams following the trail of transactions found that MDBs exposures to coal via holdings in other financial institutions. Rather than actually turning away from the underlying activity, MDB lending to coal had been passed through a different channel. From a legal ‘form’ perspective, the loans were to financial intermediaries. But from a substance perspective, they were still lending to coal but now with less transparency.

As high climate-risk industries seek more finance from financial intermediaries (private credit funds and non-bank lenders) and in turn, more global banks seek to channel finance through these intermediaries, it is essential that disclosure regulations and carbon accounting keep pace to ensure a fair view of the underlying reality. Without this, there is a real risk of ‘emissions laundering’ – an all too familiar analogy for all bank employees trained to look out for the ‘layering’ approach of money laundering.

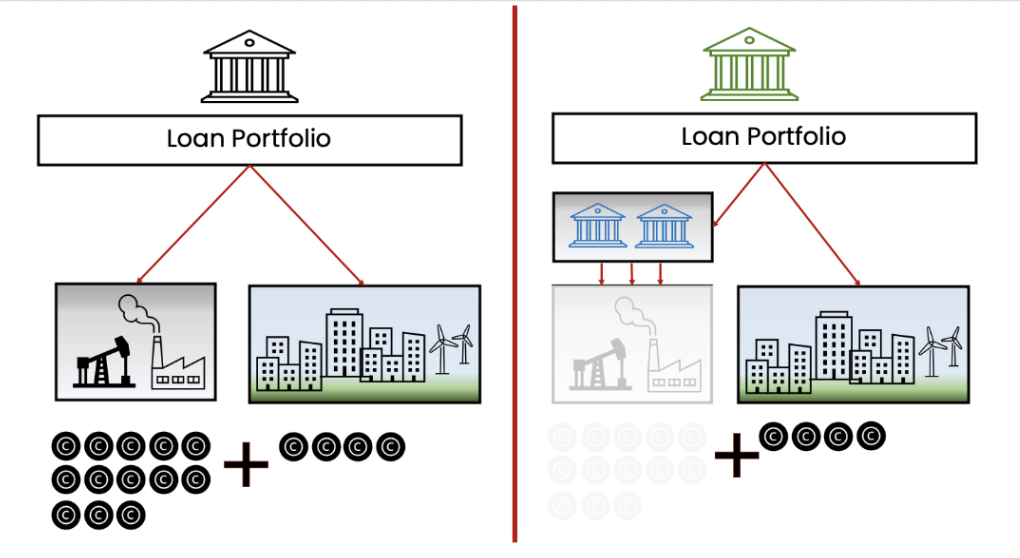

Figure 1. The impact of financial intermediation on climate-related finance and financed-emission disclosures.

Without the principle of “full look-through,” the introduction of financial intermediation (on the right) would not reveal the underlying carbon emissions.

Discovering the uncomfortable reality behind the layers of financial transactions is something the world, and in particular financial regulators, have seen before. On Monday 15th 2008 many institutions were checking to see if they had exposure to Lehman Brothers. Anxious calls came down from boardrooms. Some initially had reassuring responses – “No, we have no positions with Lehmans.” Calm was restored. Until a few days later when a nervous follow-up call revealed that “Actually, as it turns out, quite a few of our positions with others may have been exposed to Lehmans and we may be at risk ourselves.” It's the difficulty of having layers of intermediation in finance. Often these arrangements are set up to optimise financial performance (whether for reasons of tax or reallocating risks) and can become quite convoluted. Other times, the arrangements are there to insert degrees of separation between the ultimate owner and the activities on the ground, obscuring the relationship from view and avoiding scrutiny.

Wouldn’t this degree of forensic disclosure, if required by regulators, become onerous for banks to report on? It’s true that simpler transactions structures would be far easier to report and lead to fewer preventable surprises in the financial system. Perhaps making disclosure regimes more onerous for convoluted arrangements designed to obscure transparency, could promote better culture and behaviours. But with increasing access to data from organisations like the Carbon Disclosure Project and the new Net Zero Data Public Utility co-created under the umbrella of GFANZ, there are no excuses for banks choosing complex structures to avoid true and fair disclosure of the underlying climate risks and impacts.

With the global temperature increase hitting 1.5 degrees in 2024, we should be bracing ourselves for climate risks cascading through the financial sector. We need an effective financial disclosure regime to account for the true impact of climate risks. This means closing the loopholes for emissions laundering through financial intermediation, peeling back the layers and looking through to the underlying activities and their associated emissions. Today, a group of experts, practitioners and global stakeholders signed a letter of support of reform by the Basel Committee recommending they enshrine the principle of ‘full look-through’ and ensure that climate-related financial disclosures unequivocally prioritise substance over form.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision: Disclosure of climate-related financial risks https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d560.pdf

Substance over Form https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100540166

How MDBs Support Fossil Gas through Financial Intermediary Investments

https://re-course.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Still-Bankrolling-Climate-Change-1-1.pdf

Barclays, Societe Generale, Deutsche Bank Tap into Private Credit Market

Glen Jordan

Sustainable Lifestyle · Sustainable Living

Gokul Shekar

Corporate Sustainability · Sustainable Business

Barnabé Colin

Biodiversity · Nature

Eco Business

Sustainable Finance · Adaptation

The Wall Street Journal

Labor Rights · Public Governance

Australian Financial Review

Sustainable Finance · Power Grid