A shift in Power: How Africa can take control of its energy future

Unsplash

Unsplash Unsplash

Unsplash· 5 min read

For decades, African leaders have outsourced the continent’s development to western aid institutions, with few development results to show for it. The continent needs to move in a new direction, particularly in the electricity sector. Despite decades of efforts, hundreds of millions of Africans still live, work and die in darkness. The only way to change that bleak fact is for African leaders to take charge of their development future and lead efforts to electrify the continent, rather than following the edicts of western institutions.

Africa is the world’s most energy-poor continent, with nearly 600 million residents lacking electricity. While other parts of the world have reduced energy poverty to nearly zero, Africa lags far behind. This affects everything from the small, but consequential (a child struggling to do homework in the evenings or a mother giving birth without power) to the big and systemic (the capacity to develop a manufacturing sector or functioning health systems).

Meanwhile, aid agencies have spent hundreds of millions of dollars on a variety of disjointed projects in attempts to close this gap. These efforts are admirable and have no doubt made some progress in expanding access, but they have been missing one critical component: leadership from Africans themselves. The majority of electricity access projects that have taken place in Africa were led, designed and implemented by multilateral organisations whose projects rarely speak to one another. This has led to the lack of a single strategic vision, short-term planning, and vulnerability to political changes in the funding organisations.

Perhaps the most obvious example of this is the devastation that the recent US administration has brought to the continent by essentially dismantling the US Agency for International Development (USAID). USAID was leading Power Africa (in partnership with the African Development Bank [AfDB]), an initiative aiming to expand access to electricity for 60 million households across sub-Saharan Africa. Power Africa now faces an uncertain future. At the writing of this piece, none of the information regarding this project was accessible on the USAID website. Some might argue that new initiatives like the World Bank and AfDB’s "Mission 300" which seeks to provide electricity to 300 million people by 2030, will fill the gap left by USAID. While this is a welcome step, the key issue remains: who is leading?

Relying on multilateral organisations to lead reduces long-term thinking and introduces non-strategic whiplash. USAID’s Power Africa aimed to end energy poverty by 2030, a wildly unrealistic goal that required African countries to quickly follow USAID’s strategy, no matter what was being worked on before. Now that the program is likely to end, these countries will have to quickly jump onto the next bandwagon when a different development institution comes forward with its own plan for Africa.

By outsourcing the responsibility for strategic planning to outside institutions, the continent has left itself vulnerable to the whims of voters and politicians who are far removed from the consequences of action or inaction. This has not worked. But there is another way. Rather than fearing the loss of US aid, African leaders, particularly at the AfDB, should be emboldened to develop and implement their own strategy for expanding electricity access across the continent.

Electricity is a necessary precondition for economic development. There is no positive future for Africa without first providing this critical resource. Electrification is too important to Africa’s future for its leaders to simply follow the priorities of others. Yes, funding is important, and multilateral organisations have a role to play, but the leadership and strategic vision must be led by Africans. Here, there is an opportunity to learn from other parts of the world that have successfully expanded electricity access in a short period of time.

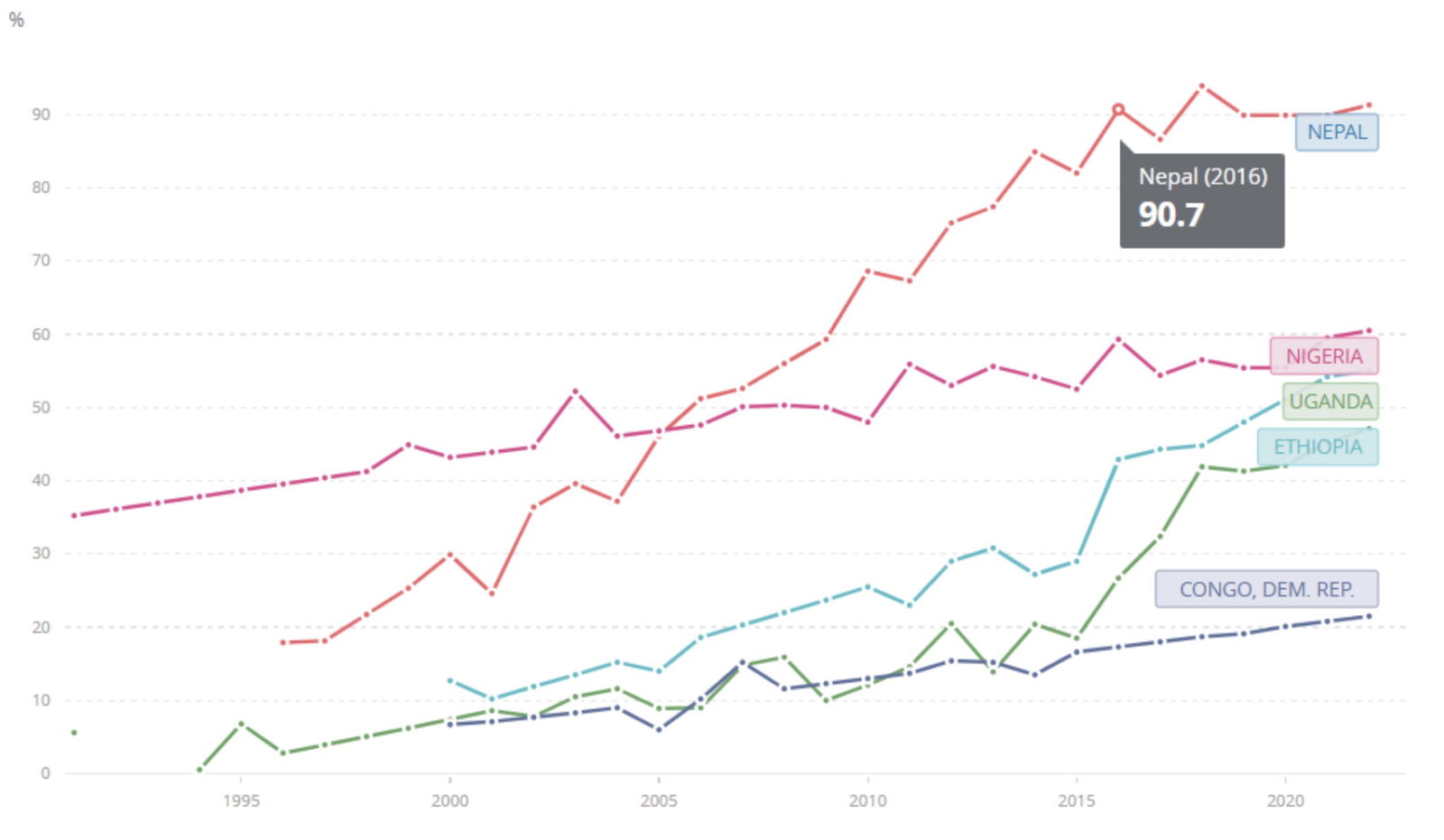

Nepal is a developing country in South Asia, with a GDP per capita slightly less than the average in all sub-Saharan African countries and similar to that of Ethiopia. 30 years ago, Nepal and most African countries began at similar levels of electrification. But, while Nepal has been able to increase electricity access from approximately 20% in 1995 to more than 90% today, in most African countries, less than half of the population has access.

Electricity access in & over the year

Nepal was able to achieve this in the span of less than one generation by allowing for private sector participation, leveraging multiple funding sources through bilateral and multilateral arrangements, prioritising its local indigenous resources, and adopting a mix of both on-grid and off-grid solutions through a dedicated institutional framework. Importantly, many of those projects were led by the Asia Development Bank (ADB) and the Nepalese government, not far flung aid organisations.

The AfDB is well-positioned to do the same in Africa. The specific methods could look different in African countries, but the lesson is the importance of regional leaders taking the lead and determining what methods will be valuable in their local settings.

By taking the lead, AfDB can resolve many of the issues that plagued previous attempts at expanding access: vulnerability to other countries’ politics, short-termism, and disjointed planning. AfDB should develop a long-term energy plan, focusing on specific local needs and locally-available energy resources. The AfDB should then coordinate multilaterals, donors and private investors, bringing others onboard to a strategy that African leaders have developed, rather than jumping onto those funders’ pre-developed plans. The AfDB should create an energy coordination body in order to align financing (donor and private capital), pool resources, avoid duplication, and ensure that all players are driving towards a single aligned strategy.

Taking these steps can then allow Africa to close some of the other gaps in the ecosystem, including potentially increasing private sector participation through regulatory changes, improving grid infrastructure, and improving local capacity. All of this can only be done after African leaders decide to develop their own plans and priorities, rather than following those of others. Until then, efforts to expand electricity will be thwarted by political changes in other parts of the world or stunted by short-term thinking.

illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

Alex Hong

Energy Transition · Energy

illuminem briefings

Hydrogen · Energy

illuminem briefings

Energy Transition · Energy Management & Efficiency

Financial Times

Corporate Governance · Oil & Gas

Forbes

Green Hydrogen · Ethical Governance

BBC

Renewables · Energy