A COP27 guide for decoding Article 6 negotiations: the evolution, the fundamentals, and the needs

· 13 min read

UNFCCC is currently holding the 27th Conference of the Parties (COP 27) in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt between 6-18 November 2022. As the adverse impacts of climate change become more visible, the seriousness of the attention that are withdrawn by climate negotiations as part of the COPs increases every year. Today several climate action authorities and experts, including myself, believe that the UN Summits refer to a never-ending chain of inconclusion. When it especially comes to the most historically critical and plugged issues of UN climate negotiations such as carbon markets, many confusions in understanding the future destination of global climate action air. For instance, addressing the current carbon roadmap included in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement and the required future adjustments have been one of most effort consuming topics in the last three COPs.

In 2018, the first version of The Paris Agreement Rule Book had been achieved thanks to COP24 Katowice negotiations. The content of the rule book has then given the first signals on the upcoming refreshment of discussions of global carbon markets after more than a decade of silence. Following this development, although COP25 has not been hosted too carbon focus centric, COP26 has been concluded by intense carbon markets negotiations that could be the most serious ones in COP history since the Kyoto Protocol which kicked off the carbon markets discussion around the world.

UNFCCC organized its 3rd Conference of the Parties in 1997 with a well-framed objective which is introducing a global contemporary market-based decarbonization instrument called carbon markets (in addition to possible physical reductions) in 1997 Kyoto. Although the idea that framed the Kyoto Flexibility Mechanisms was unique at that time, it couldn’t go beyond the diplomatic romance due to several reasons some of which I try to address as part of this article.

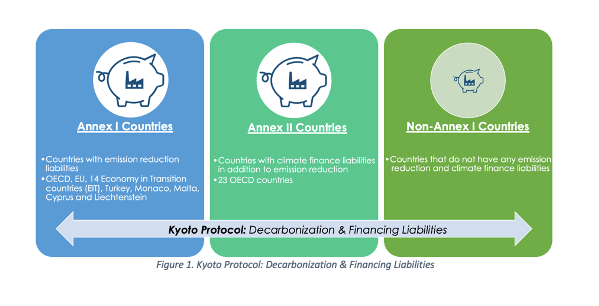

First of all, as can be seen in Figure 1, the Kyoto Protocol has been designed to put liability on the Annex-I countries (i.e., developed nations or the big piggybank - this approach is defined as top-down politics that is upper-level centric in the business/action hierarchy chain) by excluding the decarbonization ownership of developing nations. However, it could not achieve the desired climate finance mobility and emission reduction volume because climate action requires a cooperative approach that also involves non-Annex I countries (i.e., developing nations or the small piggybank).

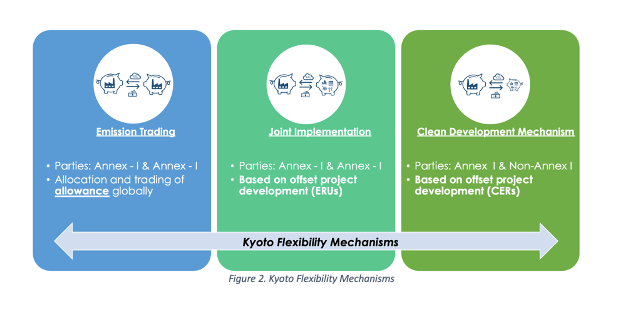

Secondly, global actors of climate action including the UNFCCC Secretariat were not ready to adopt the Flexibility Mechanisms considering their complexities in implementation. As shown by the Figure 2, it has introduced three flexibility mechanisms that aim to drive market-based emission reduction in Annex-I countries.

Although the main driving force behind the Kyoto disappointment was a basic non-compliance that resulted from the fact that almost none of the Parties has kept the promises given against the treaty within its operational timeline, the complexity of the Flexibility Mechanisms has also contributed to the failure. The complexities of the Mechanisms can be addressed as follow:

Kyoto Protocol Era has been over for climate action by leaving a legacy on several technicalities and practicalities that still drive today’s carbon market dynamics in post the Paris Era. Also, we have seen that another mechanism called Voluntary Carbon Market was born in 2006 as part of this era by referring to the lessons learnt from Kyoto Mechanisms and benefiting from the mother carbon standard CDM for feeding world’s carbon offset demand. Addressing the correlation of these two important decarbonization actors carefully would ensure the one’s understanding on Article 6 negotiations.

Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM) is an international carbon market which has been established as an alternative to the Kyoto Mechanisms and does not specify geographical restrictions for carbon project development and offsetting and operates by completely voluntary commitments. The market is driven by several carbon standards that include but are not limited to Verified Carbon Standard, Gold Standard, Global Carbon Council, Cercarbono etc. that issue carbon certificates/credits from the emissions reductions occur anywhere in the globe. As soon as an emission reduction activity meets the principles and requirements of these standards along with CDM’s, it is possible for them to develop their carbon projects and issue the associated carbon credits that can be voluntarily traded for carbon neutrality claims.

Democratization of carbon offset markets was the main need behind the rise of a parallel carbon market to Kyoto Protocol that have been criticized for significant environmental and social impacts resulted from the carbon offset projects that have been developed as part of the CDM. Consequently, the major buyers that drive the CDM market started withdrawing their investments from the carbon offset market. Moreover, the accounting issues on offset unit issuance has also impacted the credibility of the Kyoto Mechanisms. Assigned Carbon Units (ACU) allocated for Russia considering the former Soviet Union Countries’ liabilities results in an unsafe emission reduction activity. Many buyers from the Annex I countries like Japan has refused to buy emission reductions that are widely known as Hot Air[1]. Thus, voluntary carbon market could get a chance to well penetrate the carbon offset market by taking the lead from the CDM thanks to necessary environmental, social and technical integrity adjustments done in carbon offset project development and audits.

In response to all the concerns, the VCM has tried to evolve to a better integrated market practice. In this respect, we could see that many leading carbon standards have introduced smarter and stricter reporting requirements for carbon offset projects in which several environmental and social parameters are dictated to monitor to ensure the project’s contributions to sustainable development objectives.

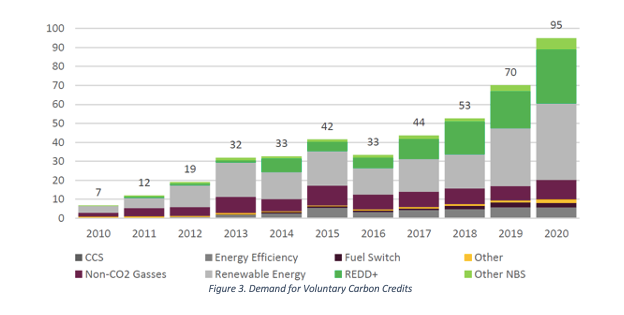

A study published by Trove Intelligence in 2021 has revealed that the demand for voluntary carbon credits has increased significantly in last 3 years (Figure 3)[2]. This continuous demand observed in last years has driven the VCM to achieve a market value of more than 2 billion USD today and could be worth upward of $50 billion in 2030, said McKinsey[3]. Although the voluntary offset price uncertainty remains its existence, no doubt that VCM has ensured a desired level of carbon offset liquidity that likely to drive reducing emissions globally. However, final rounds of negotiations that have been circulated over carbon markets during COP26 say that VCM’s evolution is yet to be done. The Paris Agreement Article 6 has also some requests from the VCM to ensure future carbon integrity.

In 2015, the Parties have adopted the most comprehensive climate action protocol in the history called The Paris Agreement after intense negotiations as part of COP 21 in Paris. With this new protocol, a new era in which the collective actions are required to limit global warming well below 1.5 Celsius Degree by 2100 has started. The collective action as part of The Paris Agreement has been defined as referring to pledges that shall be done by each Party via a diplomatic paper called Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC). In this way, The Paris Agreement imposes a bottom-up model of policy to all parties to bear balanced responsibilities in global action and makes it distinguished from Kyoto Protocol’s top-down politics.

Among all the verticals in The Paris Agreement, decarbonization would be the most challenging one. Especially considering the nature of bottom-up politics that puts emission reductions liabilities on each party, the desired reduction goal that has become even more complicated to achieve in new climate regime dictated. The Paris Agreement offers different decarbonization instruments to cope with this complexity. Article 6 of the Agreement has been designed to facilitate the efforts for market-based emission reduction by carbon markets.

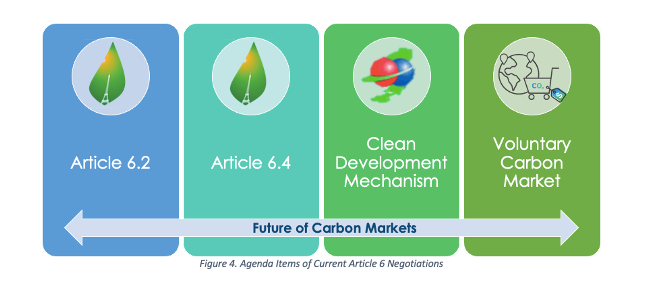

As previously discussed, there are three practices that drive today’s carbon trading transactions which are Clean Development Mechanism, Voluntary Carbon Market and Emission Trading System (at national and regional capacities). Article 6 negotiations aim to facilitate these three carbon market practices to achieve better accounting and integrity safeguards. In response to this need, UNFCCC has published Glasgow Climate Pact that has introduced four main current agenda items for Article 6 negotiations as shown in Figure 4 at the end of COP 26 in Glasgow.

The agenda items can be summarized as follow:

COP 26 negotiations have started the first real Article 6 discussions that will shape the future of carbon markets. However, as discussed, there is a lot more to discuss and decide that also makes COP 27 another suspect for becoming an important milestone in UN climate negotiations history.

The expectation from COP 27 is significant considering the intense agenda on Article 6 negotiations, especially by carbon finance beneficiaries. Among many issues that require clarification on the future functions and business flows of carbon markets, some more dynamic issues than others shall be resolved urgently to prevent a potential crash in the market as we have observed during Kyoto Era. These issues can be addressed as follows:

The Paris Agreement treats carbon emissions as a sovereign liability. So, Article 6 has shown a firm approach to treat decarbonization activity as a national asset, unless they are authorized for international claims owned by third parties. Thus, as the locomotives of the VCM, the carbon standards are expected to lay the foundations of the structure that will facilitate the carbon market actors to operate the authorization activity itself in two ways in my opinion:

As experienced in the Kyoto Era, failures in determining the baseline of a decarbonization may result in a very dangerous complexity for the environmental ambition in a decarbonization scheme which is known as Hot Air. Carbon Market Watch has addressed this concern its technical proposal published in 2019[5]. Basically, falling into a failure in determination of the Paris Agreement’s baseline could potentially create between 18.7 and 28.3 GtCO2e worth of credits or hot air which can be traded without reducing a single tonne of greenhouse gas emissions.

Among all other precautions to avoid from Hot Air, one shall be the major priority that only emission reductions that take place after 2020 should be used towards the NDCs. The other one should be setting another baseline criteria for emission reduction activity start date. Parties shall be conservative with the proposed emission reduction activities to their NDCs. For example, in the least ambitious pathway, only those emission reduction activities starting their emission reduction activities on 4 November 2016, the date when Paris Agreement entered into force, should be covered in NDCs. In brief, avoiding from Hot Air will firstly enhance the credibility of the corresponding adjustments consequently the Paris Agreement as well.

COP26 results say that the current CDM projects can be functional till 31 December 2025. However, no decision has been made on the future of already issued CERs’ functionality beyond this date. Thus, another decision shall be made for future CER transactions.

[1] https://www.reuters.com/article/btscenes-us-climate-japan-idUKTRE4B24CN20081203

[2] https://trove-research.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Trove-Research-Carbon-Credit-Demand-Supply-and-Prices-1-June-2021.pdf

[3] https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/a-blueprint-for-scaling-voluntary-carbon-markets-to-meet-the-climate-challenge

[4] https://www.globalcarboncouncil.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Standard-on-Avoidance-of-Double-Counting-V1-1.pdf

[5] https://carbonmarketwatch.org/publications/empty-targets-how-to-avoid-trading-of-hot-air-under-the-paris-agreement/

Illuminem Voices is a democratic space presenting the thoughts and opinions of leading Sustainability & Energy writers, their opinions do not necessarily represent those of illuminem.

illuminem briefings

Geothermal · AI

illuminem briefings

Electric Vehicles · Green Tech

illuminem briefings

Electric Vehicles · Public Governance

Eco Business

Sustainable Finance · Public Governance

Carbon Herald

Carbon Removal · Corporate Governance

Responsible Investor

Sustainable Finance · ESG